Strength training remains an under-utilised tool to improve performance in endurance sports despite recent evidence showing beneficial outcomes (Blagrove, Howatson, & Hayes, 2018). Concerns about slowing down, gaining muscle mass and the perceived opportunity cost of spending time performing strength training rather than doing endurance training prevent many endurance sports athletes from the benefits of strength training.

Why is this the case?

Before we discuss strength training for endurance athletes there are three primary physiological determinants of endurance sports performance that we need to acknowledge. The combination of these three factors form the primary physiological and biomechanical determinants of endurance sport outcome.

· VO2 max – the maximal amount of oxygen that can be consumed during aerobic exercise. This can be viewed as the overall CAPACITY of the body to use oxygen to perform work.

· Blood lactate markers – when our muscles use oxygen to create energy a waste product called lactic acid is formed. The blood lactate threshold refers to the maximal amount of oxygen that can be consumed before lactic acid accumulates and causes a reduction in work capacity. Blood lactate markers can be viewed as the COST of muscle metabolism.

· Economy – reflects the oxygen or energy cost of sustaining a given sub-maximal running velocity. This is a measure of how efficiently you use oxygen at submaximal levels and is determined predominantly by neuromuscular factors. Movement economy can be thought of as the overall EFFICIENCY of the body to generate energy.

A recent systematic review by Blagrove et al (2018) (Blagrove et al., 2018) reviewed 24 studies of 469 trained (>6 months) middle and long distance runners to assess the effect of strength training on the above three physiological determinants of performance. The review only included studies that had a control group of endurance only training and included strength training interventions using either heavy resistance training, explosive resistance training or plyometric training between 1 and 4 x per week.

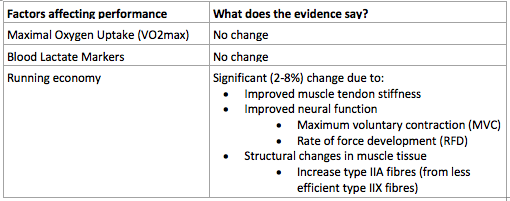

The results of the review are included in a table 1.

Factors affecting performance

Table 1. Results from Systematic Review of Blagrove et al (2018)

The review also found that while strength training did NOT improve VO2 max or blood lactate levels, they were not negatively affected. In addition, the athletes that performed strength training achieved a higher terminal velocity in a maximal aerobic running test i.e. they improved their running velocity significantly more than matched controls that only did endurance training.

Improvements in running economy, measured as the oxygen or energy cost of running at a given speed, hold the biggest key for endurance athletes to improve their performance. Running economy was improved by three main mechanisms:

1. Improved muscle tendon stiffness

a. Muscle tendon stiffness refers to the bodies ability to utilise the stretch shortening cycle to generate force. Put simply, rather than the muscles having to generate all the force to propel the body forward each step, the muscle tendon unit can store elastic energy from the previous step and ‘release’ it into the following step. Think of an elite runner and how they seem to effortlessly bounce along the track verses a beginner that plods along. Who is running more efficiently?

2. Improved neural function

a. Strength can improve by two primary ways:

i. Greater coordination of the muscle unit

ii. Larger cross-sectional area (size) of the muscle fiber

b. Strength training in endurance athletes works by increasing the maximum voluntary contraction and the rate of force development i.e. better coordination between the nerve signal and the muscle unit

3. Structural changes in muscle tissue

a. There are different types of skeletal muscle fibers that each have specific qualities. Strength training converts the large fast twitch highly fatigable (type IIX) fibers to the smaller fast twitch more efficient (type IIA) fibers.

Figure 2. Proposed mechanisms by which short term and long term endurance performance can be improved from the addition of strength training to the ongoing endurance training plan. (Aagaard & Andersen, 2010)

Interestingly, including strength training did not result in an increase in muscle mass despite participants getting significantly stronger. This is because performing a high volume of endurance training stunts the intracellular hypertrophy response normally associated with resistance training (Wilson et al., 2012) (Nader, 2006). This suggests that strength training in endurance athletes improves strength via neural changes i.e. greater coordination of muscle firing and faster rate of contraction rather than by increasing the size of the muscle.

Besides the performance benefits, strength training is also a key component of most injury prevention programs. Runners are known to have a high overall musculoskeletal running related injury (MRRI) incidence of 19.4-79.3%. (van Gent et al., 2007) The most common MRRI is medial tibial stress syndrome which is known to have several strength related risk factors i.e. low calf power and poor glute medius strength (Galbraith & Lavallee, 2009). In this way, strength training not only helps to improve performance but can help in building resilience to common running related injuries.

In summary - strength training can significantly improve running economy, running velocity and reduce time lost to common running related injuries without causing an increase in weight, muscle mass or negatively affecting VO2 max or blood lactate markers.

Which leaves me with the question…

When integrating strength training into an endurance training plan, athletes should look to work with an experienced coach that understands your injury history, training history, goals and has experience writing strength programs for running based athletes.

Many endurance sports athletes have little to no experience with strength training and for this reason the strength training program must be planned, periodised, supervised and progressively overloaded with detail and care.

For more information about strength training for endurance sports athlete’s feel free to reach out.

Written by Cameron Dyer – Physiotherapist and Athlete Rehab Specialist

References:

Aagaard, P., & Andersen, J. L. (2010). Effects of strength training on endurance capacity in top-level endurance athletes. In (Vol. 20 Suppl 2, pp. 39).

Blagrove, R., Howatson, G., & Hayes, P. (2018). Effects of Strength Training on the Physiological Determinants of Middle- and Long-Distance Running Performance: A Systematic Review. Sports Medicine, 48(5), 1117-1149. doi:10.1007/s40279-017-0835-7

Galbraith, R., & Lavallee, M. (2009). Medial tibial stress syndrome: conservative treatment options. Current Reviews in Musculoskeletal Medicine, 2(3), 127-133. doi:10.1007/s12178-009-9055-6

Nader, A. G. (2006). Concurrent Strength and Endurance Training: From Molecules to Man. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, 38(11), 1965-1970. doi:10.1249/01.mss.0000233795.39282.33

van Gent, R. N., Siem, D., van Middelkoop, M., van Os, A. G., Bierma-Zeinstra, S. M. A., Koes, B. W., & Taunton, J. E. (2007). Incidence and determinants of lower extremity running injuries in long distance runners: a systematic review. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 41(8), 469-480. doi:10.1136/bjsm.2006.033548

Wilson, M. J., Marin, J. P., Rhea, R. M., Wilson, M. C. S., Loenneke, P. J., & Anderson, C. J. (2012). Concurrent Training: A Meta-Analysis Examining Interference of Aerobic and Resistance Exercises. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 26(8), 2293-2307. doi:10.1519/JSC.0b013e31823a3e2d